Cartographies of Distance

in L. Kurgan and D. Brawley, Eds. (2019) Ways of Knowing Cities. pp 250-72.

excerpts

Upfront Postscript

Eleven days after an earlier version of this text was presented at the Center for Spatial Research’s Ways of Knowing Cities conference at Columbia University, Waldo Tobler passed away at the age of eighty-eight. The talk featured work in progress and new opportunities for constructing urban knowledge by clarifying the premises of spatial research, by returning to and reestablishing some first principles of cartographic analysis. What had started with thorny but straightforward research questions about inequities in everyday urban experience had come to present far thornier and circuitous epistemological and methodological questions. In trying to map known differences between individuals and groups, I found myself up against fundamental questions about how we know cities through mapping at all. More appropriately, I was up against the limits of common cartographic thinking—questioning the ways knowledge is produced through relationships drawn on a map.

Tobler was not explicitly referenced in the talk, but these questions are impossible without his contributions. Implicit throughout the project, and throughout this text, is the impact of his First Law of Geography. What follows is an attempt at taking that law seriously—by not taking it for granted—perhaps more seriously than it was intended. Everything is indeed related to everything else. And near things are more related than distant things. I remained convinced: somewhere in the many meanings of related and the changing definitions of near and distant lie the questions of how we construct and navigate the human environment. From the local causes and effects of globalization to remarkable shifts in worldwide demographics to the appropriation of virtual space as public space, the qualitative and quantitative relationships between near (and less near) things speak to both how we make the world in which we live and how we live in it together. (252)

from “the Cartographic Fates”

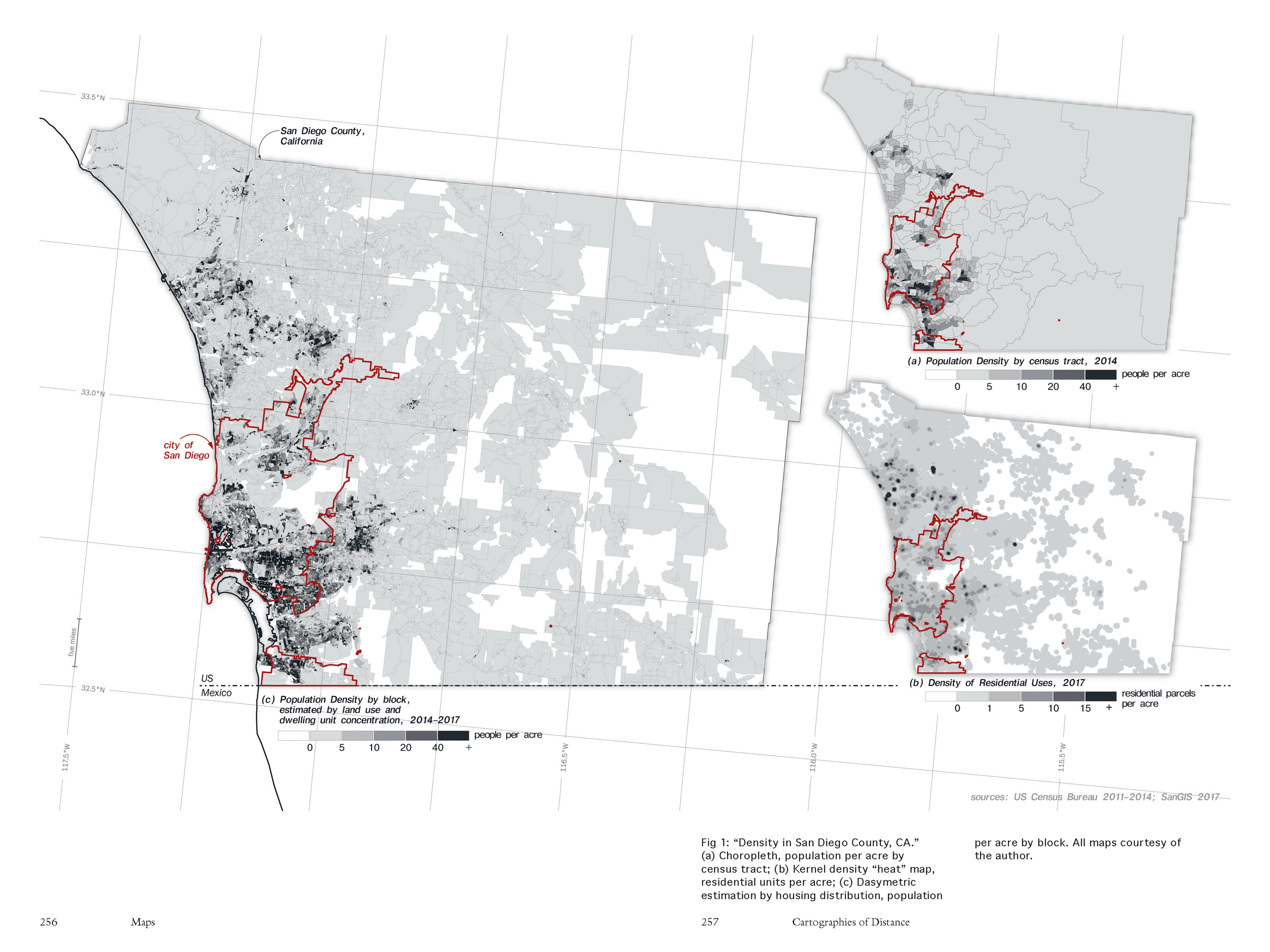

Distance may not be dead anymore—at least not as an empirical measure of the geometrically traversable ground between known, finite locations—but she isn’t quite a phoenix yet either. Distance is still struggling to rise—overshadowed by her sisters Location and Area, obscured by their digital, ready-made traces and mapped manifestations including the dropped pin, the assemblage of dots into densities, and their aggregation into the choropleth and “heat” map. Whether for policy-making or market analysis, whether identifying food deserts or strategizing health care or planning emergency response, the bigness of our data and the hunt for user-friendly, human- and machine-readable patterns have conspired in favor of mapping by default settings. The dominance of Area and Location and the dominance of their representations speak to the dominance of one back-and-forth process of analytical mapping; one way of understanding space through points, lines, and polygons; one cartographic container into which we continue to compress and contort what we know about cities. (255)

from “Early Experiments in Mapping Distance and Difference”

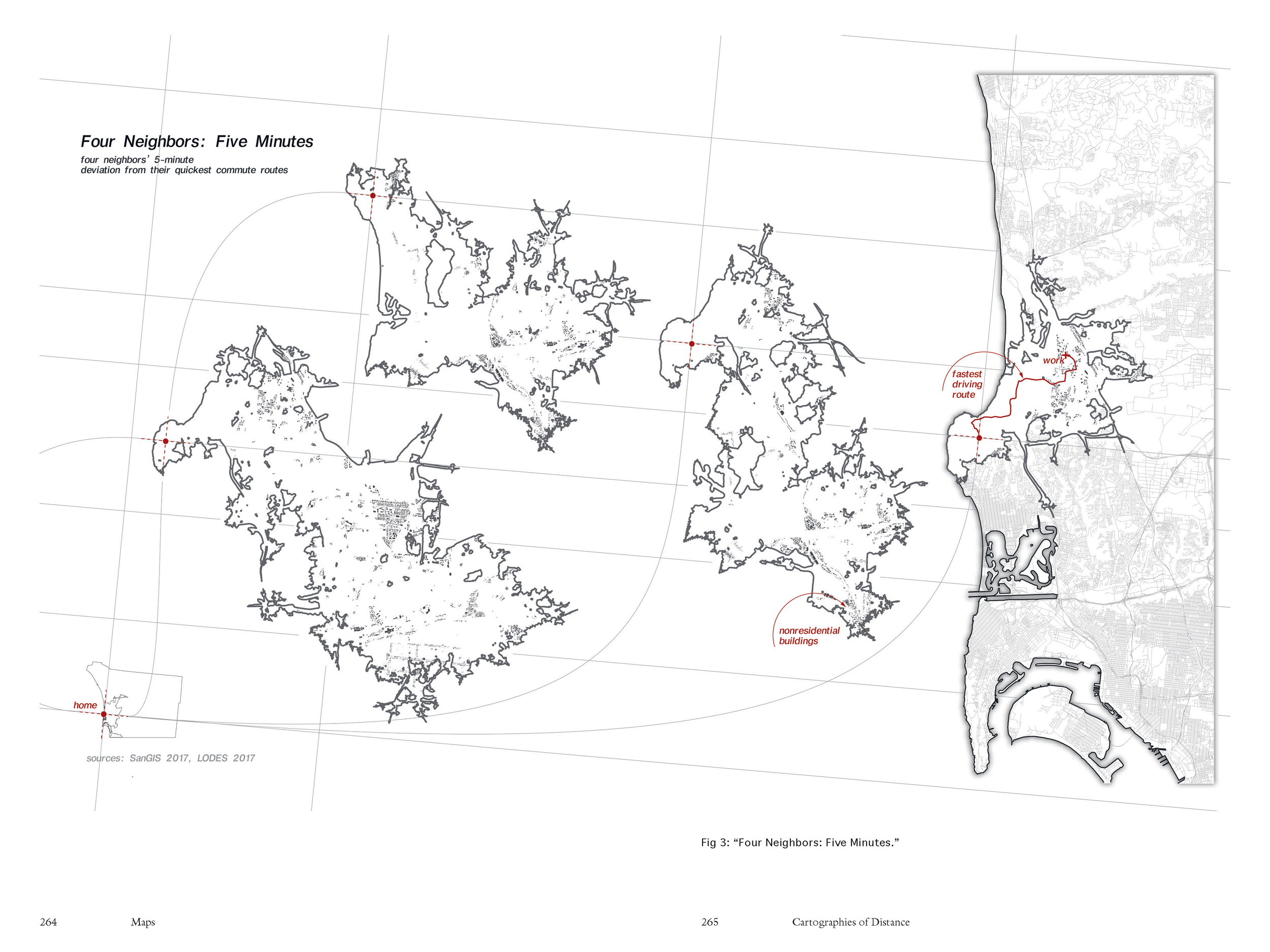

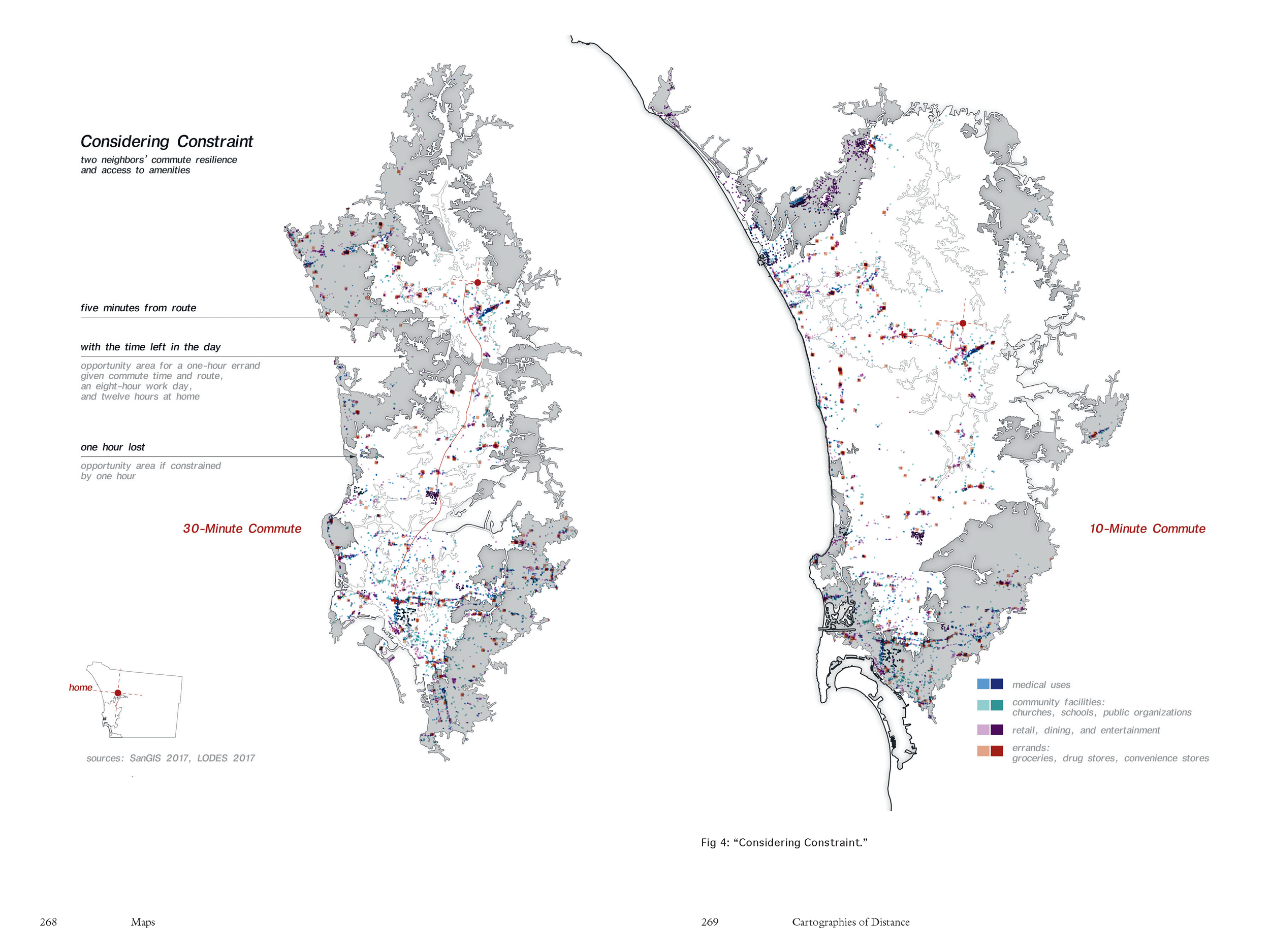

Our standard frameworks for interrogating distance-based access to the city are geometrically straightforward and rather computationally attainable. We measure either from one location to another or outward in unchallenged, incremental units of feet, miles, or minutes. Though we might not always use these resultant areas as aggregation units, we deploy these distances to create areal descriptors of accessibility, of neighborhoods, of catchment, and of association and similarity. We deploy both approaches in the planning of transit systems, zoning regulations and incentives, real estate investment, and customer bases or market analyses. We rarely, if ever, question whether movement through these areas or the time available for such movement is uniform, finding it much harder to render the constraints on distance resulting from who we are and the lives we live there. (259)

[…]

By all accounts, any definitional understanding of distance as simultaneously dependent upon all locations should worry most map users. In an era of GPS-enabled and personalized wayfinding, the map already knows its distances as a function of its locations: embedded information that we must trust if the map is to serve as a tool for finding anything. But deriving geometry is not the same as reading spatiality. Mapping to find lived distance presupposes that the map—its frame, its scale, its perspective, its contents, and its authority—is unstable. Mapping to empower distance means mapping in search of a cartographic framework that can accommodate difference without flattening or normalizing it, that demands the rigor of systematic analysis without claiming comprehensiveness, and that leverages the quantity of our collected geographic information without the seduction of Haraway’s “god trick.” (263-6)